This series will recount the history of the mafia in Florida over four articles, with the help of expert interviews and rare pictures.

This third article covers the government’s crackdown on Florida organized crime beginning in the 1950s. However, governmental action turned into more than just eradicating criminal behavior. Instead, as federal and international intervention ramped up in Florida mafia affairs, gang members and associates found themselves recruited into shady plots involving global politics and assassinations of world leaders.

This article lays out Florida organized crime events from 1950 until about 1970 and picks up from where the series’ previous installment, “From Prohibition to Prosecution,” left off.

The Florida Mob and the Kefauver Hearings

The Mafia’s ominous silhouette loomed over most of the country by 1950, stretching from New York’s boroughs to Hollywood, California, and down to Florida’s sandy beaches. Organized criminals with whole or partial ties to mafia families had overrun the gambling industry, hotel industry, movie production, labor unions, narcotics smuggling, and much more countrywide.

With the organized crime anthill steadily growing and finally becoming too large to ignore without getting bit, the federal government had no choice but to intervene. The Senate established the Special Committee to Investigate Crime in Interstate Commerce in May of 1950, marking the first major, concentrated effort to understand organized crime in America.

The committee included five senators from five different states, with the most notable of the bunch being Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee, whose southern drawl and favorite coonskin hat made him easily identifiable, trademark American, and, simply, very good television when questioning witnesses.

The Kefauver Committee, as it came to be known, went on a countrywide tour investigating Mafia activities. It conducted 27 hearings in 14 cities, with over 600 witnesses testifying in total, including some of organized crime’s most notorious names. The goal of the committee: to show evidence that there was a national syndicate of organized crime working across state lines to collude, corrupt, and racketeer.

The Sunshine State Gets Subpoenaed

In Florida at this time, the Trafficante crime family was the most prominent mafia presence around Tampa, with the aging Santo Trafficante, Sr. at the helm with his son, Santo Trafficante, Jr. The Tampa clan had their hands in drug smuggling, illegal gambling (in the form of bolita), and ownership of several businesses and other rackets in Florida. The Trafficantes, with their fluency in Spanish, also maintained stakes in a handful of casinos and hotels in Cuba.

Around the middle of the state, the lesser-known yet prevalent and influential “Cracker Mob” operated under the leadership of Harlan Blackburn, who worked closely with Sam Trafficante, another Trafficante sibling, to cut the Tampa family in on the profits and allow the cracker gangsters freedom to operate their gambling businesses, moonshine stills, and other rackets in central Florida.

I sat down with author, organized crime expert, and Tampa Bay resident Scott Deitche for more information, and he notes that the relationship between the Trafficantes and the Cracker mob was mutually beneficial.

“They had a really good partnership, where they didn’t necessarily step on each other’s toes, but they complimented each other,” said Deitche. “Blackburn had the backing of the [Tampa] mafia, and the mafia had his network of guys that were operating in these areas that the mafia didn’t have a stronghold, so it was a win-win for both sides.”

In Miami, the other prominent Florida mafia hotspot by 1950, nearly every well-known family from the Northeast’s big cities had some piece of the underworld pie, like ownership of illegal casinos, hotels, bookmaking operations, and more.

All the major Mafia families agreed that Miami would be an open city since its founding just three decades earlier, so it was relatively easy for associates from everywhere to fly down and plant roots in and around the teeming city. Meyer Lansky was one of the most significant presences in Miami from early on, but author Avi Bash reckons in his book, Organized Crime in Miami, that every crime family had an active presence there by 1950.

With such a bustling organized crime presence throughout Florida, the Kefauver Committee made Miami one of its first stops on its nationwide tour in the summer of 1950 to investigate organized crime there.

The committee heard 13 witnesses, subpoenaed the books of six hotels in the Miami area, and asked for the records of many more people suspected of being connected as they tried to turn the heat up on Florida’s mafia members. The committee’s findings were substantial and revealed that mafia activity ran up to the highest level of political office in Florida, proving how murky Florida’s organized crime waters really were.

Crooked Cops

The Kefauver Committee found several police officers in and around South Florida, such as Sheriffs James Sullivan of Dade County and Walter Clark of Broward County, lined their pockets considerably while in office without the salary raises to match. Gangsters were reportedly paying an estimated $1 million annually in bribes to law enforcement officials.

Already having been removed once and reinstated by Florida governor Fuller Warren, Sullivan quickly resigned again when he heard that the Kefauver Committee was coming back for a second stop in Miami in 1951. He reportedly took tens of thousands of dollars from mobsters for his re-election campaigns and used the money to pay his house off and build another for his family.

Broward’s Walter Clark was reportedly on the take from mob casinos, allowing games to go on unimpeded in several hotels and pocketing a cut of the earnings for himself.

A Guilty Governor?

Speaking of Governor Warren, the committee found his hands weren’t exactly clean of mob scent. Warren, elected governor of Florida in 1949, came under fire from the committee for allowing illegal gambling to become so pervasive in his state. How could he not notice?

Despite getting summoned three times and ultimately subpoenaed to appear before the committee, Warren never went on record and spoke at the hearing. He refused to cooperate, citing a conflict of interest between the federal government and state’s rights.

As you can imagine, his refusal didn’t exactly make him look innocent. In addition to claiming that Warren regularly overlooked illegal gambling in Florida, the committee alleged that Warren’s 1948 run for governor was financed by mob money. He supposedly got funding from the owner and operator of several dog racing tracks in Florida, who also happened to be a long-time friend of notorious gangster Al Capone.

Booming Businesses Get Busted

Speaking of the dog tracks, they were corrupted, also. The committee believed that Capone and his associates had controlling interests in several throughout Florida, including the Miami Beach Kennel Club near South Beach.

The committee also found out the alarming extent to which the mob infiltrated South Florida’s glitzy hotel scene.

In the 1950s, major mafia members from New York, Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, and more had apparent financial interests in the Wofford Hotel, Rony Plaza, Deauville, Sans Souci, Saxony, Versaille, and Eden Roc, to name a few in Miami Beach.

According to the committee’s report, Frank Erickson and his New York gang make their headquarters at the Wofford and the Boulevard Hotels, the Detroit gang at the Wofford and the Grand Hotels, and the Philadelphia gang at the Sands Hotel in Miami Beach.

Further up the coast, Meyer Lansky and his crew either owned or had a piece of the Colonial Inn and Club Boheme in Hallandale, the Greenacres Gambling Casino in Greenacres, the Boca Raton Hotel, the Hollywood Yacht Club, the Island Club, and Club Collins. In fact, the committee claimed that Meyer Lansky was connected to every major gambling house in South Florida.

Lastly, the Kefauver Committee uncovered and effectively busted the S&G Syndicate, which was a bookmaking operation that had been operating basically free and clear at hotels throughout Miami. One testimony stated that bookies openly walked around the pools and cabanas, asking sunbathers for their bets.

In 1948 alone, the S&G Syndicate reported taking over $26 million in bets, with the committee estimating their profits to be about $2 million for that year. This is, of course, assuming that their accounting was accurate and not underestimating anything.

Government officials raided S&G offices after 1950 and made life a lot harder for them afterward. It became much more difficult for bookies to operate, and law enforcement brought charges against most of the syndicate’s members.

Hearts and Minds

And, perhaps most importantly for the Kefauver Committee, the general public could see these criminals and mobsters questioned and exposed like never before thanks to a new invention called the television, which was exploding in popularity around this time

Estimates state around 30 million viewers tuned into the Kefauver hearings, making it one of the most watched spectacles in young television history. Movie theaters even ran free screenings of the hearings.

The Tampa Fallout

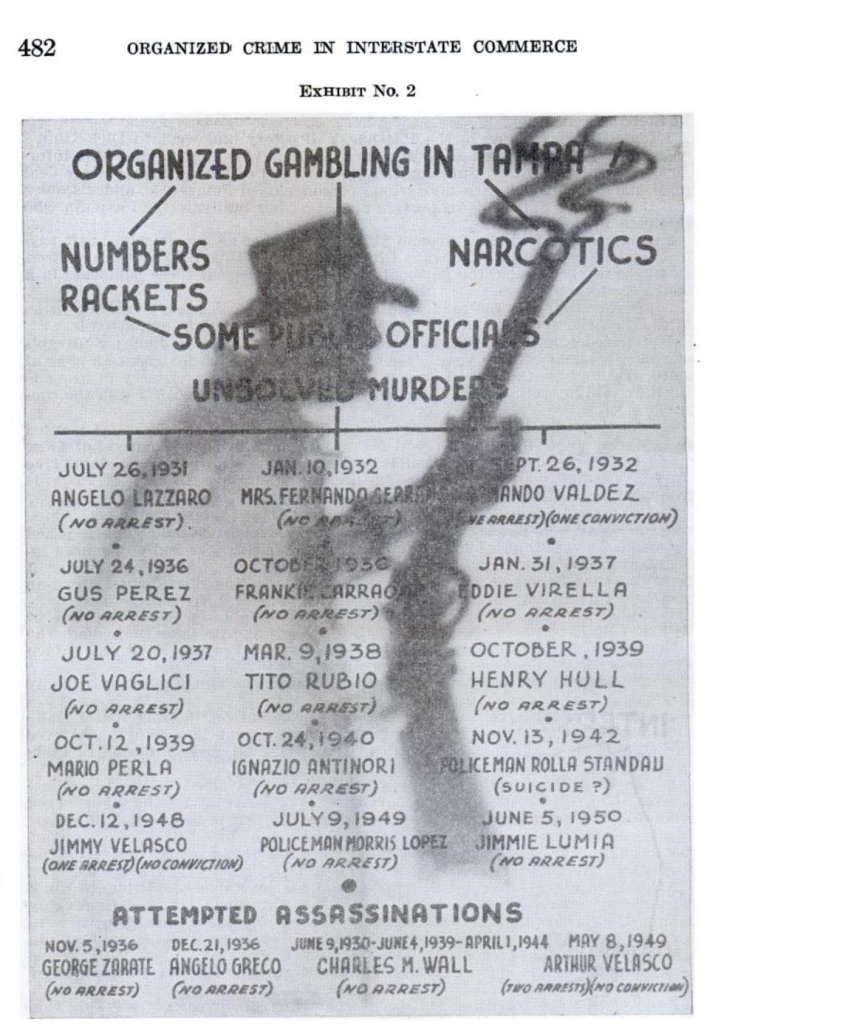

The committee also stopped in Tampa in 1950 and learned about further mob-tied police and political corruption in the city, with one of its highest-profile witnesses none other than old-timer and former Tampa mob boss Charlie Wall. By this time, in 1950, Wall was pushing 70 years of age and quite detached from the mafia picture he once ruled in Tampa, usurped by the Trafficantes and their competition.

Wall painted a detailed picture of the Tampa mafia to prosecutors and the public with colorful stories of his past in and around the city. Wall’s testimony, of course, ruffled some feathers in the mafia community, and it wouldn’t go unnoticed.

Deitche states that the Kefauver Commmittee’s effect on public perception was profound.

“It really reinforced what the regular citizens of Tampa long suspected – that the mafia significantly infiltrated Tampa politics and regular operations, and I think the same was true in Miami,” said Deitche. “It really laid bare how ingrained the mafia were in Miami by 1950.”

In Tampa, a bit of a power vacuum formed around this time, partly due to the Kefauver Committee. Salvatore “Red” Italiano, who the committee named the top man in the bolita rackets, fled before Kefauver and his band of merry crime busters visited the city.

James Lumia, another powerful Tampa mafia figure who worked with Italiano and had a possibility of underworld power in the city, was murdered in 1950. The killing officially remains unsolved to this day.

Trafficantes Take the Reins

With the number of potential top dogs thinning, Santo Trafficante, Sr. became the undisputed mafia boss of the Tampa area in the early 1950s until he died of stomach cancer in 1954. Old Charlie Wall never got a shot to reinsert himself into power. He was murdered in his home in 1955, with his testimony to the Kefauver Committee likely serving as the death warrant.

With no one else to challenge him, the path was now clear for a second-generation, Spanish-speaking, Italian mobster to take the mafia throne in Tampa. His experience and connections he had been cultivating throughout his life were about to pay off.

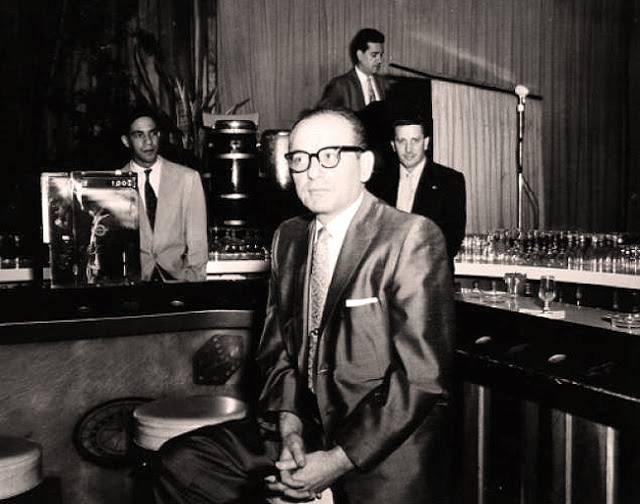

Santo Trafficante, Jr. ascended to the boss of the Tampa mafia and much of Florida around 1954, quietly putting him among organized crime’s elite and most influential figures nationally. While not as bold, flashy, or public as New York or other Northeast mafia families, Trafficante’s control of Florida and influence beyond state lines was nothing to scoff at.

As Deitche relayed in our interview, Mafia colleagues held Trafficante in high regard, and they often sought his advice on Florida matters.

“Even though Miami was an open city, everyone kind of paid their respects to Trafficante. Certainly from his contemporaries, he was viewed very favorably,” said Deitche. “You never heard a lot of things being plotted against him. He was always asked his opinion on things that had to do with Florida, even though he didn’t really control all of the Miami area – it was kind of out of respect.”

The Apalachin Bust

Despite the Kefauver Committee’s findings, direct criminal charges were hard to come by due to the lack of hard evidence and direct connections to the crimes being investigated. However, the committee showed that the Mafia’s impunity was starting to wane. Law enforcement became more and more aggressive as the years went on.

Evidence of Trafficante, Jr.’s standing amongst Mafia elite became evident in 1957, when he, along with over 60 other national Mafia members, was apprehended in 1957 in Apalachin, New York, in one of law enforcement’s most successful bust-ups of a Mafia meeting.

Due to recent turmoil in the Mafia ranks, a New York capo named Joseph Barbara had decided to host a mob summit at his getaway in rural Apalachin for Mafia families from around the country to iron things out. Apalachin cops staked the mansion, raided, and rounded up many of the attendees, including Trafficante. Although no charges stemmed from the incident, it made Trafficante very wary of his position and power.

Although the Tampa mob wasn’t one of the largest mafia families in terms of members, it still held influence on a national scale. Deitche reports that at its height in the 1950s and ’60s, the Tampa mob had about 40 core members, not including associates, which puts it on par with families like Kansas City and St. Louis. This is still much smaller than the New York gangs. The Genovese family, for example, had nearly 300 made guys at its height.

A Cuban Connection

Although Trafficante always spent a good amount of time in Cuba, he began to take up a more permanent residence after the Apalachin bust with the heat on the Mafia reaching uncomfortable levels stateside.

According to Deitche, the Tampa mob’s relationship with the Cuban underworld dates back to the 1920s when Ignazio Antinori was the Tampa boss. Once he was murdered in 1940, the door was open for Santo Trafficante, Sr. to build upon what was available. He, along with his son, were the top Tampa mafia members operating in Cuba. The other most notable Florida organized crime member with large stakes in Cuban businesses was Meyer Lansky out of Miami.

The Trafficantes’ Cuban businesses mainly consisted of narcotics smuggling and hotel and casino operations. Santo Trafficante, Sr. was likely extremely influential in smuggling heroin and cocaine from Europe through Cuba and ultimately into Tampa. Trafficante, Jr. continued this business after his father’s death.

Lansky, the other major mob figure in Cuba, befriended corrupt Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. Batista allowed Lansky to own and operate several hotels and casinos in Cuba while receiving a skim of the profits.

“In the case of Cuba, Lansky was kind of the dominant Mafia figure there, but I would put Trafficante easily as the second most influential Mafia figure in that pre-Castro Havana era,” said Deitche in our interview.

On the relationship between the two, Deitche states that he’s found mixed reports.

“I’ve read that they didn’t necessarily like each other, but kind of respected each other. I’ve read where they were more cordial to each other than [some] would have you believe. They certainly had a lot of mutual friends and business partners.”

Even though they might not have been best friends, the two Florida mafia heavyweights worked in tandem peacefully to reap massive rewards in Cuba.

According to Deitche, Trafficante, Jr. helped staff Lansky’s prime casino in Cuba, the Riviera, with people from Tampa’s Ybor City. Meanwhile, Trafficante, Jr. also owned or invested in several of his own hotels and casinos in Cuba, including the Sans Souci, the Capri, and the Hotel Deauville.

Castro Turns the Tides

Everything changed for Lansky and Trafficante when Fidel Castro violently took over rule of Cuba in 1958, showing that the Florida mafia’s influence extended deep into Cuba’s veins.

Castro’s intense brand of communism wasn’t on display from the very beginning, so Trafficante didn’t realize his Cuban businesses were in danger until it was too late.

Although he was on fine terms with the ruling Batista party, Trafficante actually discreetly financed Castro’s rebellion by helping supply Castro and rebels with arms to overthrow the existing government. He was playing both sides.

However, this didn’t provide Trafficante or any other mobsters in Cuba with enough goodwill for Castro to spare them once he gained power. Castro became staunchly anti-corruption and anti-American and made it a point to publicly destroy the mobsters’ casinos. Lanksy fled the country shortly after Castro took over.

But, Trafficante, Jr. didn’t immediately leave. And, for the first time in his life, the Tampa mob boss was imprisoned – and it wasn’t even in America!

In the summer of 1959, Cuban authorities apprehended Trafficante at his Havana apartment. They sent him to Triscornia detention camp along with several other casino workers in the country, including Jake Lansky, Meyer’s brother.

Federal Involvement Reaches Conspiratorial Heights

Famed mob lawyer Frank Ragano worked to free Trafficante, Jr. from Cuban prison. He eventually achieved his return to the States in November of 1959. After being ousted from Cuba, Trafficante, Jr. spent much of his time in Miami, where events took a turn to the unbelievable for him and other Mafia figures.

The Castro Conundrum

By 1961, the Central Intelligence Agency had already tried and failed a handful of assassination attempts on Fidel Castro, whose communist influence they believed to be a danger to United States national security only 90 miles from home soil.

With their options thinning, the CIA unbelievably recruited the help of Trafficante, Jr. and other mob figures for help with the job. They figured Trafficante’s contacts and familiarity with Castro, Cuba, and the underworld were perfect for this kind of task.

According to____, Trafficante’s first meeting with the CIA occurred in March 1961 at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach. Chicago gangsters Sam Giancana and Johnny Roselli also attended.

While the group did hatch a plot to poison Castro, it ultimately never materialized. There was not a second meeting, as the CIA decided to go a different route that eventually became the Bay of Pigs disaster.

Trafficante Jr. had financial involvement in further anti-Castro efforts and an influence on the newly sprouting Cuban Mafia in Miami throughout the 1960s. However, rumors also swirled that he was a Castro double agent, which possibly helped his release from Triscornia just a few years earlier.

Regardless of his position on Cuba, he still maintained chief power of the Tampa mob and much of the Florida mafia scene outside of Miami. Bolita proliferated in Miami with the new influx of Cubans that fled after Castro took over. Many families had hands in the game.

Additionally, mafia families from throughout the country continued to own clubs, restaurants, and hotels in and around Miami.

The JFK Conspiracy

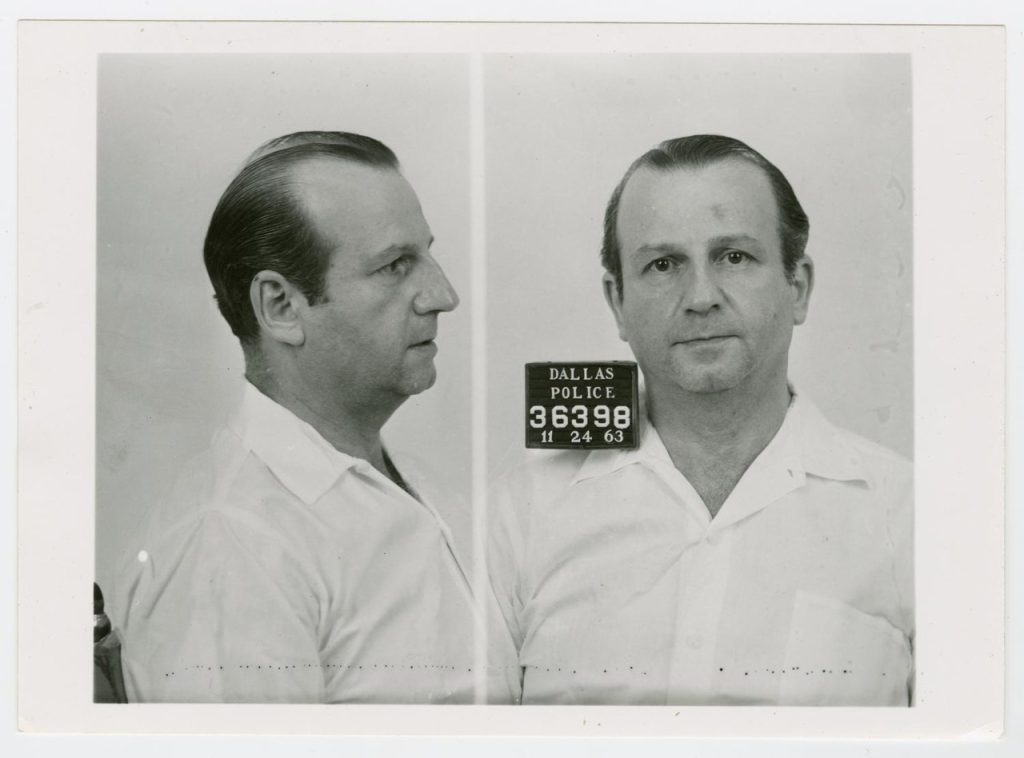

There are endless authors more qualified than me who have delved into the conspiracy theories surrounding President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. So, I won’t go too in-depth on it, but it’s worth noting that Santo Trafficante, Jr. is a cog in the wheels of one of the popular theories, and his possible involvement dates back to his detention in Cuba.

Ragano, Trafficante’s lawyer, was working to get the mafia boss freed, but he wasn’t in Cuba while doing so. He was in the States, so it wasn’t that easy to communicate with parties in Cuba at the time. The parties needed a man on the ground to help facilitate the release.

As it turns out, the man pinned for this job at the time in 1959 was Jack Ruby, who at the time was a low-level organized crime figure from Texas. Ruby, of course, later became famous as the man who gunned down JFK’s supposed killer, Lee Harvey Oswald, in 1963.

Although Ruby’s exact dates and times in Cuba in 1959 aren’t wholly agreed upon, it is confirmed that Ruby traveled to Cuba on at least three occasions. At least one of the dates aligns with when Trafficante was incarcerated. Additionally, there are eyewitness accounts that Ruby and Trafficante met, and several organized crime associates of Ruby have connections with Trafficante.

The possibility of a Ruby and Trafficante meeting in 1959 is prime kindling to fuel conspiracy theories related to mob involvement, Cuban connections, and CIA influence that all swirl around the JFK assassination and tie Trafficante and the Tampa mafia to events extending well beyond Florida’s borders.

Florida’s Organized Crime Outlook Into the 1970s

As 1970 approached, legacy Italian Mafia families still had controlling interest in Miami. The Trafficante syndicate still pervaded throughout most of the state. However, hints of change and uncertainty were in the air.

Many of the notable bosses were aging by this time, as many had been active since the 1920s. Also, government intervention had become much more commonplace since the Kefauver hearings, making business more difficult than it once was.

Also, other factors, like demographic shifts and technological advancements, created a much different world than when the Italian mob kicked off just 40 years earlier.

The series’ fourth and final installment will explain the rise of the Cuban Mafia, the fall of Meyer Lansky, and the changes in the Tampa mob as Florida’s organized crime picture morphed with age. Stay tuned.

Outstanding story, well written, couldn’t stop reading it.