This series will recount the history of the mafia in Florida over four articles with the help of expert interviews and rare pictures.

This second article outlines the mafia’s expansion and proliferation in the first half of the 20th century in Florida, where we see some of organized crime’s biggest names arrive center stage. Read article one for valuable historical context here.

Prohibition provided the perfect launching point for Florida mobsters to ramp up their activities with profitable new crimes like bootlegging liquor and opening speakeasies.

When the federal government enacted the 18th Amendment on January 17, 1920, the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages became illegal nationwide.

Despite such a righteous, upstanding, and sweeping reform, the American public still wanted to get plastered pretty regularly. Citizens still craved alcohol while it was outlawed, and mobsters nationwide were happy to jump on this opportunity. Many organized crime and mafia members in Florida would find ways to take part in alcohol sales and smuggling.

Florida’s Pre-Prohibition Landscape

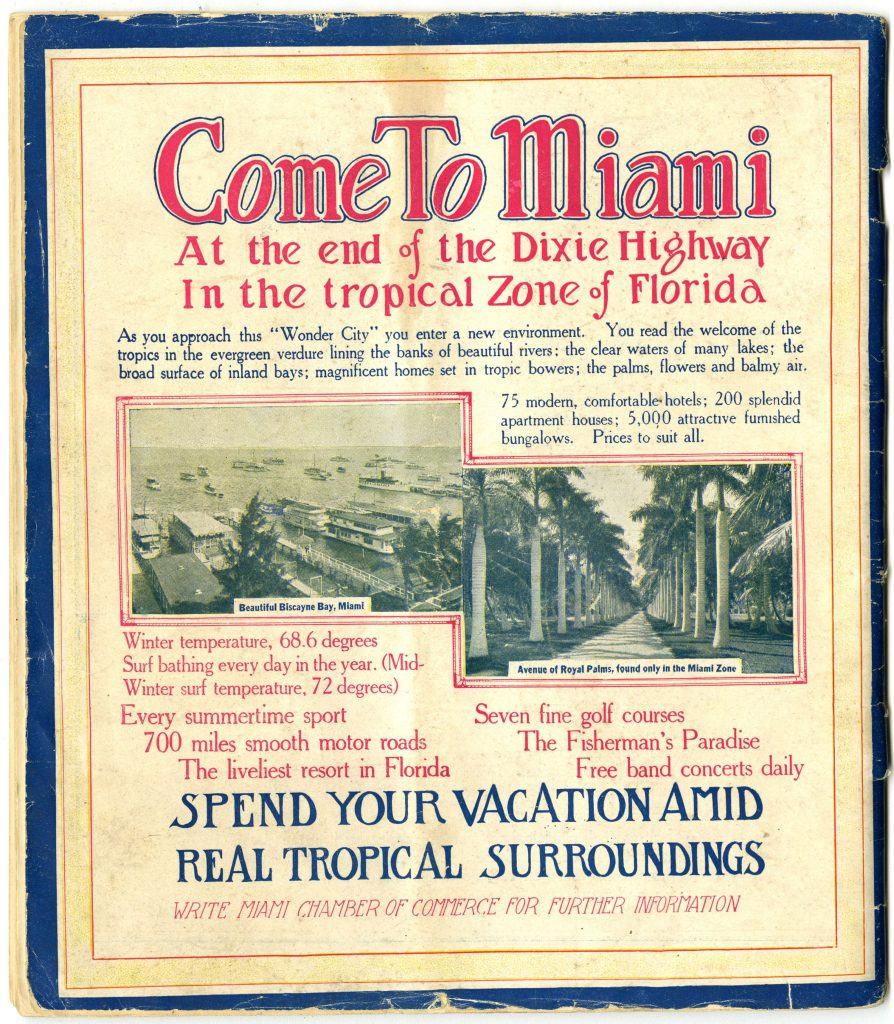

For context, Miami, now Florida’s most iconic city, was a fledgling settlement in 1920 that had been formally established only about two decades earlier. Tampa was the more populous city at the beginning of the 20th century, incorporated about 70 years earlier in 1850.

In 1920, Tampa’s population was over 50,000 compared to Miami’s 30,000. Since Tampa had been around longer, a few organized criminals in the city established themselves with other vices before Prohibition became appealing. These figures are important to mention as they’re often overlooked in Florida’s mafia history.

Jo-Jo Cacciatore and George Zarate were some of the first notable narcotics peddlers in early Tampa. Cacciatore established a drug network in historic Ybor City before Prohibition and expanded his operations throughout the state and beyond in the coming decades.

Zarate got his start selling morphine and eventually owned and worked in speakeasies and gambling houses in Ybor City, such as Podie’s Cafe, until he fled the state in 1941.

The final notable mobster in Tampa before Prohibition was Charlie Wall, son of former Tampa mayor John Perry Wall. Although the Walls were a well-connected, well-off family in early Tampa, both of Charlie’s biological parents died when he was young, perhaps helping steer him to his life of organized crime.

Charlie Wall was the most successful bolita racketeer throughout Tampa pre-Prohibition. Bolita was a Cuban lottery game that proliferated in Florida throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s before gambling was legal. Significant numbers of Tampa’s early residents (and later Miami residents) were Cuban, and their influence consistently helped bolita thrive.

For more information on major gangsters in Tampa and the build-up to organized crime in Florida before Prohibition, watch part one of the Florida mob video series.

With narcotics smuggling, namely heroin, and bolita already on the map in Florida, Prohibition brought another lucrative activity for organized criminals and mafia members to generate cash in the Sunshine State.

Prohibition Brings Profits to Florida

Florida was a great place to give Prohibition the middle finger. Both of the state’s coasts were prime for rum-running. Smuggling liquor production ingredients and finished alcohol products from Cuba and the Bahamas was easy since they were just a boat ride away. Several instances of alcohol smuggling are recorded in Pinellas County and South Florida, while the largely remote Everglades and Central Florida served as liquor still havens.

In St. Petersburg

For example, organized crime author Scott Deitche, who I interviewed for this article and the corresponding video series on this topic, writes in his book The Silent Don: The Criminal Underworld of Santo Trafficante Jr that Al Capone, Johnny Torrio, and other members of the notorious Chicago clan purchased acres of land around Gulfport, just west of a growing St. Petersburg, in the late 1920s and reportedly smuggled booze from the Gulf of Mexico.

The Gulfport Historical Society further reports that Capone may have had a stake in the Jungle Prada nightclub, the area’s first nightclub still existing today as the Jungle Prada Tavern, where underground tunnels were supposedly built to help smuggle alcohol.

In Central Florida

Additionally, the sparsely populated middle of the state was a convenient place for moonshine stills that could easily supply willing buyers on either side of them.

Deitche mentions the importance of an oft-overlooked faction of Florida mobsters called the “cracker mob,” who primarily operated in central Florida under the discretion of the Tampa mafia family.

“The cracker mob had gambling houses, speakeasies, and moonshine stills out in areas like Lakeland, which was a popular hot spot for them,” Deitche stated during our interview. “Already, you start seeing some of the Tampa guys going out there and interacting with them.”

Harlan Blackburn headed the cracker mob. Blackburn was a life-long criminal and expanded his group’s influence throughout central Florida, but he always made good with the Tampa family.

“Surprisingly, moonshine stills existed, and the Tampa mafia had interests in them, into the 1970s,” Deitche continued, “You see police reports of moonshine stills being run by guys from the cracker mob into the 1970s.”

The Land Boom Beckons

Crucially, Prohibition also coincided with the Florida land boom of the 1920s. As temperance posters blanketed crowded cities in the northeast, real estate development companies spread advertisements for prime, undeveloped land in sunny Florida.

Miami and the settlements around it attracted tens of thousands of residents from the north, mafia members among them. Miami’s population surged from just under 30,000 in 1920 to over 100,000 people by 1930.

Many other cities at the center of the boom, such as Miami Beach, Miami Springs, Miami Shores, Coral Gables, Hialeah, Hollywood, and Boca Raton, would all have a notable organized crime presence in the decades that followed.

The new residents in and around Miami had to have a way to quench their vices of drinking and gambling somehow. Florida mobsters were happy to help out.

Backroom casinos with free-flowing alcohol were common in many of Miami’s new, posh hotels, such as the Sunny Isles and the Roman Pools. Miami Beach became a major tourist location where liquor and gambling were readily accessible if you knew where to look.

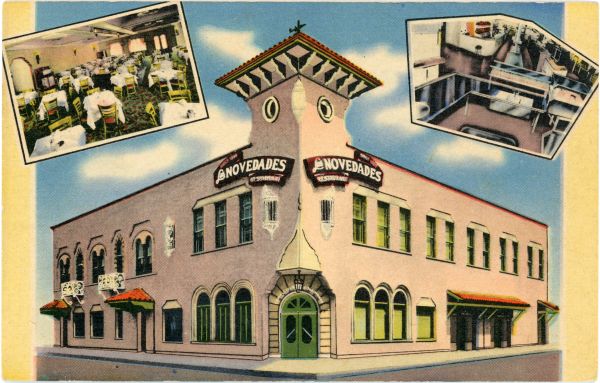

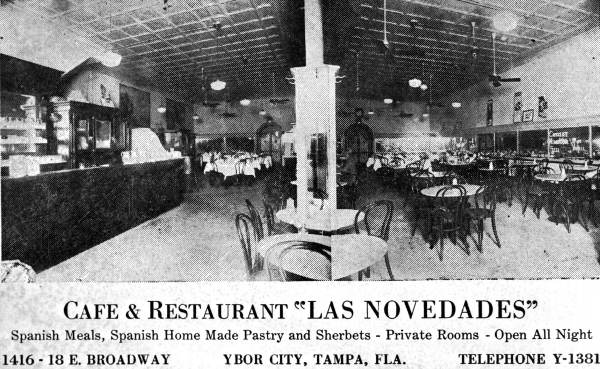

Similarly, on the state’s opposite coast, it wasn’t uncommon to find citizens neglecting Prohibition openly in Tampa, sitting outside and drinking publicly at one of the many trademark cafes and restaurants in Ybor City, such as the storied Las Novedades.

Miami and surrounding cities were prime receiving points for alcohol coming from the Bahamas just a short way away. The Florida Historical Quarterly states that Dade, Duval, Hillsborough, and Palm Beach counties presented the greatest problems for Prohibition enforcement.

Mafia Families Get in on the Action

By this time, Florida’s reputation as a booze-reeking organized crime hotspot was apparent. It attracted notable mob interest from the northeast, where the American Mafia originated.

According to Dietche in his book Cigar City Mafia, New York mob boss Vincent Mangano, one of the original bosses of the Five Families, backed two Tampa residents and their claim to Mafia leadership in the area around this time.

Mangano backed the Diecidue family, who had been in the Tampa mob picture since the late 1800s and would be in the frame for a long time to come. The family’s patriarch, Alphonso, and many of his sons were crucial members of the Tampa mafia for decades.

While profits poured in from alcohol, the popularity of bolita didn’t fade. Charlie Wall dominated the West Coast gambling underworld, running rackets in Pinellas, Pasco, Polk, Hernando, and Hillsborough counties. He also held considerable power among Florida mobsters at this time.

The Santo Trafficante Crime Family

In addition to Wall and Diecidue, another Tampa mobster was gaining traction in the 1920s by the name of Santo Trafficante, Sr. Trafficante Sr., a Sicilian, was married to Maria Giuseppa Cacciatore, the sister of early drug kingpin Jo-Jo Cacciatore.

Trafficante Sr. was a prominent bolita racketeer and allegedly also had some approval to take the underworld reins in Tampa from Joe Profaci, another Five Families boss who founded what would become the infamous Colombo family.

Trafficante Sr. did a fantastic job of staying out of headlines for the length of his organized criminal career, but his effect on the Tampa underworld shouldn’t be understated.

On top of these names, several other notable racketeers and gangsters were vying for power in Tampa at the time, like the Bedamis, another Italian family that had been around for decades at this point.

The struggle for the top spot and control of the rackets would lead to an ugly and violent period in Tampa’s history in the coming decade of the 1930s. However, while things were getting competitive and tense around Tampa Bay, organized crime life on the other side of the state was relatively easygoing.

Peace and Prosperity for Miami Organized Crime

You could say the ball got rolling in southeast Florida in 1928 when nationally notorious gangster Alphonse Capone bought a 6,077 square-foot house at 93 Palm Avenue on Palm Island, Florida for $40,000 (equivalent to over $700,000 in 2024). He soon made it his new permanent residence.

Shortly afterward, in 1929, the Capone syndicate leased the Hollywood Golf and Country Club in Hollywood, Florida. It was converted into a private gambling club and hosted world-class entertainment acts.

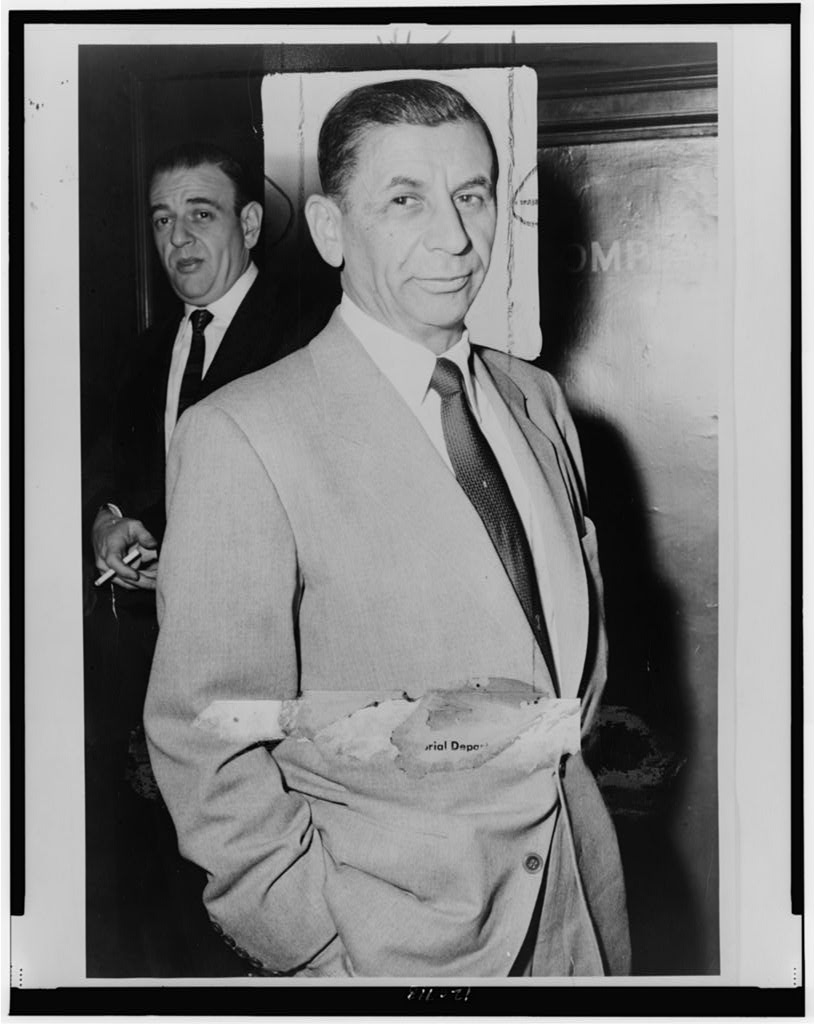

When it rains, it pours. Also in 1929, a prominent mobster from New York named Meyer Lansky reportedly purchased a home in Biscayne Bay, just south of the Miami area. Lansky, a wise businessman, was eyeing a piece of the South Florida pie for himself.

Since essentially every crime family wanted a piece of action in budding South Florida, the mafia families mutually agreed that Miami would be an “open city” where all agreed to cooperate instead of fighting for control of sectors, which historically led to turf wars in New York.

This agreement didn’t entirely prevent gang-related violence among Miami organized crime members, but it did allow the Mafia to flourish quickly in the city and many of the other new South Florida towns with less turbulence.

The Lansky Effect

By the time Lansky settled in Miami, a man named Anthony Carfano, “Little Augie Pisano,” was running gambling rackets in the city, where slot machines and punch boards were easy to find if you looked with any effort. Carfano was an associate of Mafia bosses Lucky Luciano and Frank Costello.

Lansky and Luciano were friends, which enabled Carfano and Lansky to soon go into business together in Miami. This marked Lansky’s first dip into a pool of business dealings that would eventually make huge splashes in South Florida and beyond.

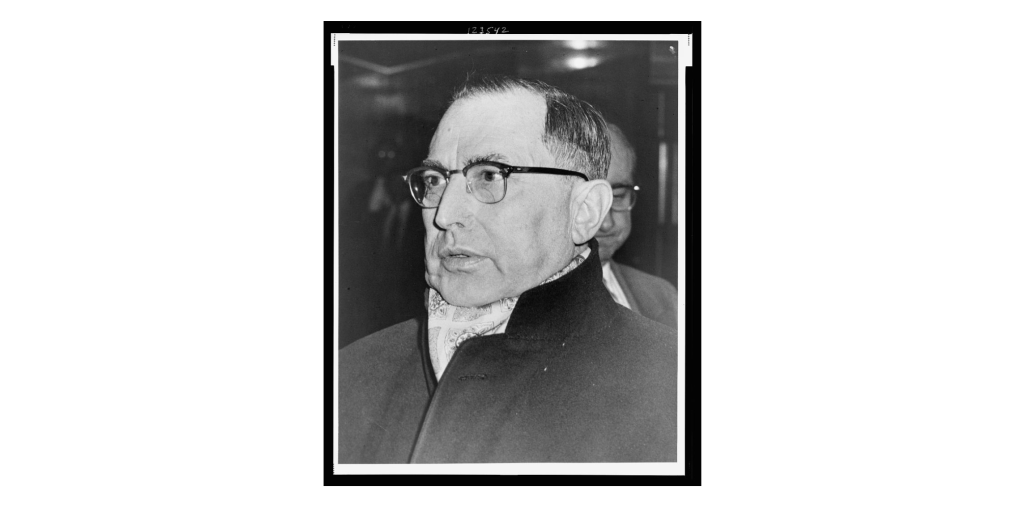

Lansky was always good with numbers. One of the reasons for his meteoric success in organized crime was his mathematical and financial abilities. He was known as the Mob’s accountant.

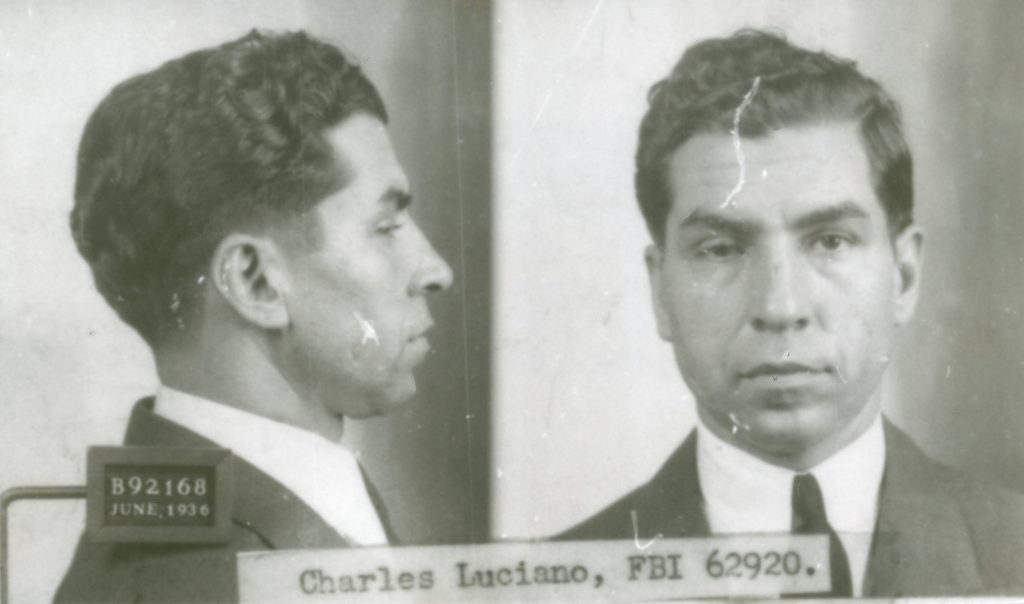

He also happened to be life-long friends with two major Mafia bosses. Lansky grew up in a working-class section of Manhattan in the early 1900s, where he befriended Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel and Charles “Lucky” Luciano when they were all young.

The trio got involved in organized crime together and ascended to become, without exaggeration, some of the most powerful mobsters in the whole country. They were crucial in reshaping the Mafia into a national crime syndicate with increased cohesion and acceptance of ethnicities other than Italians (Lansky and Siegel were both Jewish).

In South Florida, Lansky quickly began buying up firms of a certain kind: casinos, nightclubs, and racetracks. These cash-heavy, vice-related establishments were critical to mobsters as they were great for fraud and appealed to an audience always ready to spend.

Lansky was perhaps the most notable and prominent mob presence in Miami from the beginning. It wasn’t long before gang members wanting a piece of the ripe South Florida action followed, and members of the New York, Cleveland, and Detroit crime families found casinos and hotels to operate in the 1930s.

Notably, Julian “Potatoes” Kaufman of Chicago and Vincent “Jimmy Blue Eyes” Alo from the New York Genovese tree both gained firm footholds in South Florida’s early organized crime scene and exerted influence in the area.

While connected mobsters spit out new operations all over South Florida in the 1930s and 40s, the events in the Tampa underworld were becoming hard to swallow.

Turmoil in Tampa: Era of Blood

The 1930s began a gory period in Tampa’s history marked by violent gangland murders that claimed the lives of prominent mobsters and unlucky civilians. This “Era of Blood,” as it came to be called, lasted more than a decade and saw over 25 mobster-related murders in and around the Tampa area in efforts to control the rackets. Hits began in the early 1930s and escalated into slayings of big-time players.

Evaristo “Tito” Rubio, supposedly Charlie Wall’s right-hand man, was gunned down in 1938. Mario Perla, another notable Tampa underworld boss, was killed in 1939. According to Dietche, Perla had one of the largest mob funerals in Tampa’s history.

In 1940, Perla’s boss, Ignazio Antinori, one of the top drug dealers and bolita racketeers in Tampa at the time, was mysteriously murdered in the city. His case remains unsolved to this day.

It was clear by these murders that someone wanted to take ultimate control of the Tampa area. By 1940, Trafficante Sr, the Diecidues, Joe Bedami, and a Salvatore “Red” Italiano became some of the most easily identifiable top dogs in the Tampa organized crime scene.

It Runs in the Family

As is often the case, organized crime was a family business. The Diecidues and the Bedamis had multiple family members involved in the Tampa mob. So did Trafficate Sr., who groomed his son, Santo Trafficante Jr., into a promising prospect for mafia leadership while he was young.

Trafficante Sr., with his mob connections in New York, helped his son learn from the best. In the 1930s, Trafficante Jr. took trips up north to work with members of the Luchesse and Profaci crime families when he was growing up. He also went to Europe, Central America, and Mexico with his father while growing up to get firsthand glimpses of the family’s international business of drug smuggling and racketeering.

Also, with strong Cuban ties via Ybor City, the Trafficante father and son duo frequented Cuba for gambling and other business interests there. In the 1930s, Trafficante Sr. established Cuba as a major transshipment point for heroin coming from France into Florida. Both men spoke fluent Spanish, which was a huge advantage they had over most gangsters trying to make deals in Cuba.

The Picture Gets Bigger

Throughout the 1930s, Trafficante Sr worked at the top of the Tampa mafia food chain with his son, Trafficante Jr., along with the Diecidues, the Bedamis, and Charlie Wall. At this time, Trafficante Jr. also became central to gambling operations in Cuba, where fellow mobster Meyer Lansky had a dominating interest and a score of his own gambling casinos and racetracks in the 1940s with the assistance of corrupt Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista.

At this same time in Miami, the mafia was running rampant, opening and controlling all types of businesses, including restaurants, hotels, bookmaking operations, gambling houses, prostitution rings, and more.

As you might imagine, this extensive mob activity wasn’t restricted to Florida and Cuba. Organized crime proliferated nationwide in the 1930s and 1940s, from invasion of the gambling industry to labor racketeering to loan sharking to extorting Hollywood movie studios. Organized crime had become a pervasive, countrywide problem.

So, in 1950, the federal government stepped in. The Senate put together the first major committee to investigate organized crime in the country. Not only would this committee’s findings lead to several reforms and changes, but it thrust the shady work of the Mafia and its colorful characters into the national spotlight like a real-life soap opera.

Header image: Meyer Lansky, Santo Trafficante Jr. (courtesy of Avi Bash), and Al Capone